When it comes to understanding human health and disease, the narrative has long been shaped by a nature-versus-nurture debate. Are we products of our genes, or do our environments mold us more? Over time, science has illuminated a far more intricate story—one that doesn’t pit genes and environment against each other but shows how they intertwine in dynamic, often surprising ways. This is especially true when we talk about polygenic traits, which involve the contributions of many genes, each with a small effect. Add environmental exposures to the mix, and we enter the fascinating territory of polygenic gene-environment interactions.

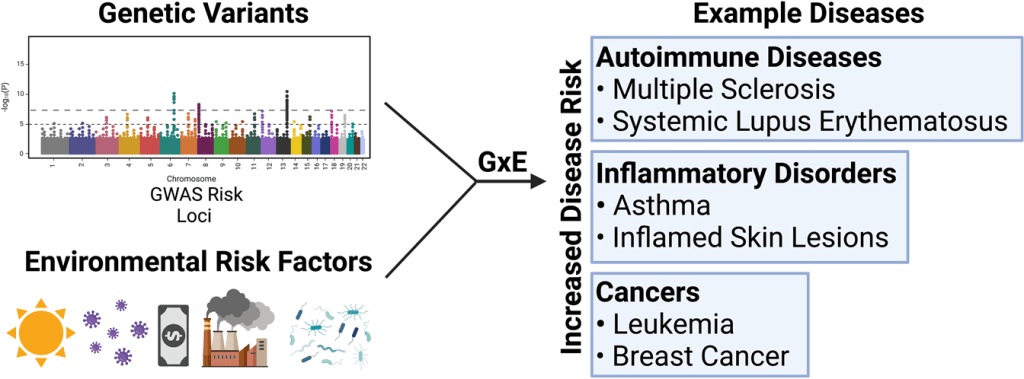

This concept sits at the frontier of personalized medicine, public health, and predictive genomics. It is increasingly clear that our risk of complex diseases—such as diabetes, heart disease, depression, and many cancers—is shaped not by a single gene or a single lifestyle factor, but by a combination of numerous genetic variants interacting with a wide array of environmental influences. These interactions are not only key to understanding why some people develop a disease while others don’t, but also to developing more accurate, personalized prevention and treatment strategies.

What Is a Polygenic Trait?

Before diving into polygenic gene-environment interactions, it’s helpful to define what a polygenic trait is. Unlike monogenic traits—controlled by a single gene—polygenic traits are influenced by the cumulative effect of many genes, often numbering in the hundreds or even thousands. Each of these genes contributes a small amount to the overall risk or trait expression. Height, intelligence, skin color, body mass index (BMI), and susceptibility to diseases like type 2 diabetes or schizophrenia are all classic examples of polygenic traits.

Because each genetic variant contributes only a fraction to the total risk or expression of a trait, polygenic traits are often highly sensitive to environmental modulation. In other words, even small environmental changes can amplify or mitigate their overall impact.

Enter: Polygenic Risk Scores

One of the most important tools in understanding polygenic traits is the polygenic risk score (PRS). A PRS estimates an individual’s genetic predisposition to a trait or disease based on the presence of multiple risk-associated variants across the genome. This score can then be used to categorize people into low, medium, or high genetic risk groups.

However, a major limitation of PRS is that it only accounts for genetic variants—it does not include environmental exposures or behaviors. This is where gene-environment interactions become critical. A person with a high PRS for heart disease, for example, might never develop it if they follow a healthy lifestyle, while someone with a low PRS might still be at risk due to poor diet, smoking, or high stress levels.

Understanding Polygenic Gene-Environment Interactions

A gene-environment interaction occurs when the effect of exposure to an environmental factor on a health outcome depends on a person’s genetic makeup. In the polygenic context, this means that multiple genetic variants interact collectively with one or more environmental exposures to influence disease risk or trait development.

For example, consider body weight. Obesity is a classic polygenic trait influenced by hundreds of genes, many of which affect appetite, fat storage, or energy expenditure. At the same time, environmental factors—diet, exercise, sleep, socioeconomic status—play a massive role. A person may have a high genetic risk for obesity, but with a balanced diet and active lifestyle, they may maintain a healthy weight. Conversely, someone with a low genetic risk might become overweight if they live in an obesogenic environment with easy access to processed foods and minimal physical activity.

Polygenic gene-environment interactions are not only common but bidirectional: genes influence how we respond to the environment, and the environment can, in turn, modify gene expression through mechanisms like epigenetics.

Case Study: Depression, Genetics, and Childhood Trauma

One of the most well-studied and emotionally impactful examples of polygenic gene-environment interaction involves major depressive disorder (MDD). Depression is a highly heritable condition, with twin studies estimating a heritability of around 35–40%. However, no single gene causes depression. Instead, hundreds of genetic variants, each contributing a small amount, collectively influence susceptibility.

A 2019 study published in Nature Human Behaviour investigated the role of polygenic risk scores for depression in combination with early-life environmental stress—particularly childhood trauma. The researchers used data from over 100,000 participants and found a striking interaction: individuals with high polygenic risk who also experienced childhood trauma were significantly more likely to develop depression than those with high genetic risk but no traumatic experiences.

Conversely, those with a high genetic risk but a stable, supportive childhood environment had a much lower chance of developing depression. This finding supports a “diathesis-stress model”, where genetic vulnerability (diathesis) is activated under environmental stress.

The implications are profound. First, they show that genetic risk is not deterministic. Second, they highlight the importance of early-life interventions, which could dramatically change the trajectory of individuals genetically predisposed to mental health disorders. For clinicians and policymakers, this suggests that targeted support and trauma-informed care could reduce the population burden of depression even among genetically at-risk individuals.

Why These Interactions Matter

Understanding polygenic gene-environment interactions has practical consequences across multiple domains:

- Personalized Medicine: Integrating polygenic risk scores with environmental and lifestyle data allows for more accurate risk prediction. Imagine a future where your genetic profile informs not only your treatment plan but also the best preventative measures for your lifestyle.

- Public Health Strategies: Knowing how environment interacts with polygenic risk can help in designing targeted interventions. For example, community programs promoting healthy eating and activity could be prioritized in areas with high obesity prevalence and where people have high genetic susceptibility.

- Mental Health: In psychiatry, where diagnosis is often subjective and treatment trial-and-error, understanding polygenic interactions could improve prognosis and guide more tailored therapies.

- Ethical and Social Dimensions: As we learn more about these interactions, it’s vital to consider equity and accessibility. Genetic testing and tailored interventions should be available to all, not just the privileged, to avoid widening health disparities.

The Role of Epigenetics

A further layer of complexity in polygenic gene-environment interactions is introduced by epigenetics—chemical modifications to DNA that affect gene expression without changing the genetic code itself. Environmental exposures such as diet, toxins, stress, and physical activity can lead to epigenetic changes that “turn on” or “turn off” certain genes.

This suggests that even if a person has a genetic predisposition, the way their body responds can be altered based on the environment. These changes can be temporary or, in some cases, persist across the lifespan—or even be inherited by future generations.

For example, a child exposed to malnutrition or high stress during early development may experience epigenetic modifications that influence metabolism, stress response, and inflammation—potentially increasing the risk for diseases later in life, particularly if they also have a high polygenic risk.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their promise, studying polygenic gene-environment interactions comes with significant challenges. One is statistical power—detecting interactions between hundreds of genes and multiple environmental exposures requires very large sample sizes and precise data. Another issue is population bias. Most genetic studies have been conducted in people of European ancestry, limiting their applicability to other ethnic groups.

Moreover, measuring environmental exposures accurately—especially over long periods—is difficult. Lifestyle factors change, memories are imperfect, and some exposures, like stress or pollution, are hard to quantify objectively.

Finally, there’s a risk of misuse or overinterpretation of genetic data. Polygenic risk scores are not crystal balls. They indicate probability, not certainty. Ethical safeguards must be in place to protect privacy and prevent discrimination based on genetic risk.

Looking Ahead

As technology advances and datasets grow, we are gradually uncovering the complex web that connects our genomes to the world we live in. Understanding polygenic gene-environment interactions holds immense potential for improving health outcomes, reducing disease risk, and designing fair, effective interventions tailored to individuals and communities alike.

In the future, routine health checkups may include both your genetic profile and a detailed environmental exposure history. Doctors might assess not only your cholesterol levels but also your polygenic risk for heart disease—then customize a prevention plan that suits both your biology and your lifestyle.

Yet, the most powerful message we can take from this science today is that genetic risk is not a sentence. It is a piece of information—valuable, but modifiable. In most cases, how we live still matters as much, if not more, than what we inherit.

Interested in learning your polygenic risk score or how your environment may be shaping your genes? Consult a genetic counselor or explore reputable genomic health platforms. But remember—genetics may load the gun, but environment pulls the trigger.

You must be logged in to post a comment.