By Iqra Sharjeel

Inspired by: CHATOMICS

In bioinformatics, we often want to understand how two genes are related. But sometimes, their relationship is affected by a third factor. Partial correlation is a statistical method that helps us find out how strongly two variables are related after removing the effects of other variables. This is especially helpful when working with cancer data, where different cancer types can affect gene behavior.

Let’s say you’re looking at how Gene A and Gene B behave in many cancer cell lines. You notice they’re highly correlated. But what if both genes are influenced by a third gene, like a transcription factor? Are A and B directly related, or is their connection only due to this third gene? That’s where partial correlation comes in. It lets us “control” for that third gene and see the true relationship between A and B.

This is especially useful in cancer studies. For example, genes like FOXA1 and ESR1 are known to be important in breast cancer. In one dataset from DepMap (a large cancer genetics resource), we saw that across all cancer cell lines, FOXA1 and ESR1 had a correlation of 0.38—a moderate connection. But when we looked only at breast cancer cell lines, the correlation jumped to 0.52. This tells us that cancer type plays a big role in their relationship.

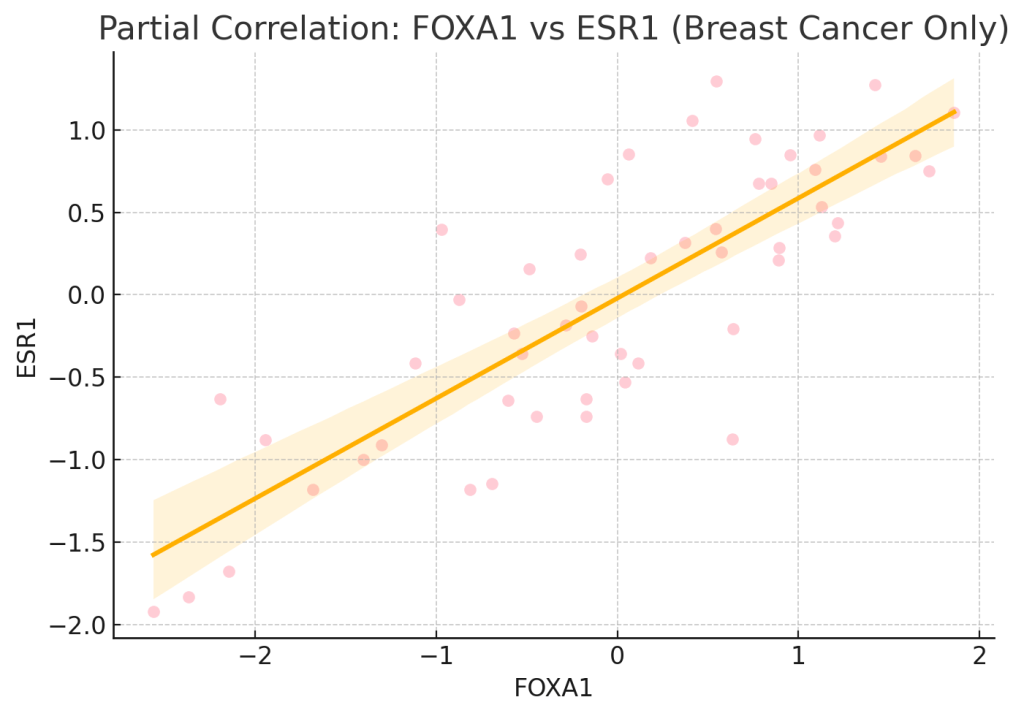

To remove the influence of cancer type, we use a method called linear regression. This allows us to adjust for confounding variables, such as the type of cancer. When we did this, the partial correlation between FOXA1 and ESR1 came out to 0.30. This means that even after removing the effect of cancer type, these two genes are still moderately related. It also means that part of the original 0.38 correlation was due to cancer-type differences.

Why does this matter? Because in breast cancer, ESR1 is often essential—it helps cancer cells survive. FOXA1 is a transcription factor that supports estrogen receptor activity, which involves ESR1. So, it makes sense biologically that these two genes are closely linked in breast cancer. The stronger correlation in breast cancer (0.52) confirms that they’re more connected in that specific context.

We calculated this using data from CRISPR gene knockout screens. These tests show which genes are essential for cancer cell survival. Lower scores mean a gene is more essential. We also used a second dataset that lists the cancer type for each cell line, so we could match gene data with the cancer it came from.

To do this in R, we loaded the data, cleaned up the gene names, and joined the two datasets together. We then used the lm() function to create a linear model, first looking at the simple correlation between FOXA1 and ESR1, and later adding cancer type as an extra variable. This second model gives us the partial correlation—a better measure of their real relationship across cancer types.

One helpful trick is to standardize the data using the scale() function. This gives variables a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, which helps make results easier to compare. When you do this, the slope of the regression line becomes equal to the Pearson correlation coefficient.

We also looked at the effect of cancer types. For example, the model showed that breast cancer lines have a significantly lower ESR1 dependency score compared to other types like adrenal gland cancers. That makes sense because ESR1 plays a major role in breast cancer biology. The regression model also showed that the relationship between FOXA1 and ESR1 is statistically significant, with a p-value less than 2e-16, meaning it’s not likely due to chance.

This kind of analysis is useful not just for individual gene pairs, but also for building gene networks. Standard correlation methods can create networks where genes look connected, but only because they share a common influence. Partial correlation helps clean this up by filtering out indirect effects. As a result, you get more accurate networks that better reflect real biological interactions.

Studies show that partial correlation-based networks reduce false connections by 30% to 50% compared to simple correlation networks. They also match better with results from lab experiments, like transcription factor binding data from ChIP-seq.

In summary, using partial correlation helps us understand the true relationship between genes by controlling for outside influences like cancer type. In our example, it showed that FOXA1 and ESR1 are truly connected across many cancer types, but their relationship is especially strong in breast cancer. This approach gives researchers a clearer picture of gene interactions, helping them identify key targets for cancer treatment.

Whether you’re studying gene expression, CRISPR screens, or building gene networks, partial correlation is a powerful tool for discovering meaningful biological relationships while avoiding misleading results caused by hidden variables.

You must be logged in to post a comment.