By Iqra Sharjeel

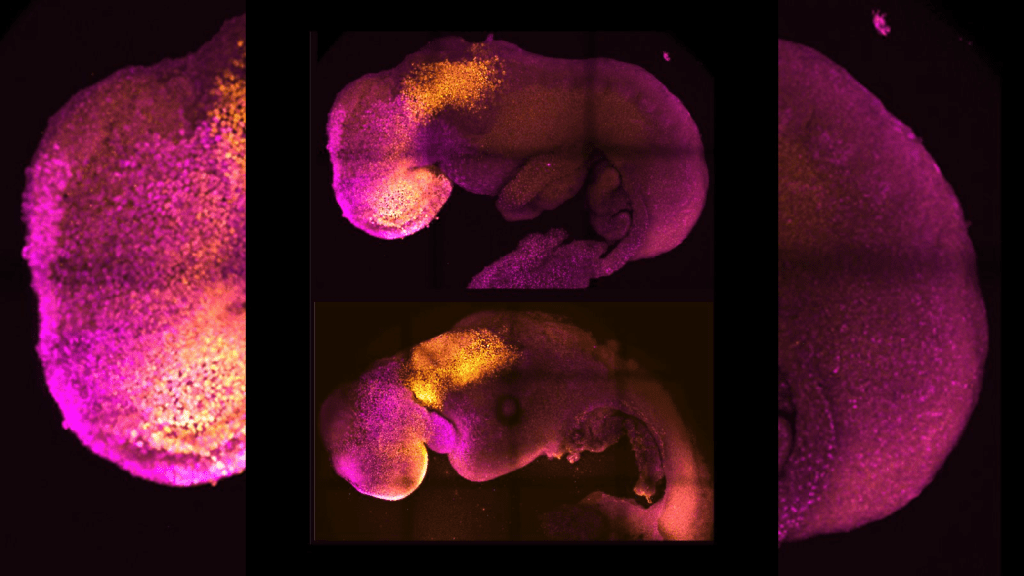

A team of scientists at the University of Cambridge, led by Professor Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, has successfully developed synthetic mouse embryos using only stem cells—without the need for eggs or sperm. These embryo models form a brain, a beating heart, and the foundation of all essential organs.

By mimicking natural embryonic development in the lab, the researchers guided three types of mouse stem cells to interact and self-organize. Using a controlled gene expression environment, they triggered the cells to communicate, leading to the creation of complex structures such as the yolk sac, heart tissue, and brain—including its crucial anterior region.

This achievement marks the furthest development ever reached by a stem cell-derived model embryo, surpassing earlier synthetic models. The results, published in Nature, are based on over a decade of research and could help scientists understand early pregnancy failures and potentially support organ regeneration.

Zernicka-Goetz emphasized the importance of the “dialogue” between embryonic and extraembryonic tissues (which later form the placenta and yolk sac) during the first critical days of development—when most pregnancies fail.

“This moment is usually hidden from us, as it happens after the embryo implants in the womb,” she said. “Our model allows direct observation of this crucial stage.”

The study also revealed that the brain’s development, especially the anterior region, relies heavily on chemical and mechanical signals from extraembryonic cells. The team demonstrated the potential of the model by disabling a gene essential for brain and eye development, replicating known birth defects in the synthetic embryos.

While this research was done with mice, the team is developing similar models for human embryos to investigate why many pregnancies do not progress past early stages. The model offers new ways to study neurodevelopment and genetic disorders, and could one day aid in growing synthetic organs for transplantation.

Zernicka-Goetz, reflecting on her career, explained how her upbringing under a restrictive regime in Poland inspired her independent thinking and resilience. Despite early discouragement, she pursued the “black box” of early embryonic development—eventually unlocking insights that were once thought impossible.

Her research has also explored genetic abnormalities such as mosaic aneuploidy, offering hope for understanding natural mechanisms that allow embryos to self-correct genetic errors.

“This is like discovering a new world,” she said. “To witness the earliest moments of life so closely is not only scientifically exciting—it’s deeply moving.”

Detailed Procedure Behind Synthetic Mouse Embryo Creation

The creation of synthetic mouse embryos represents a groundbreaking step in developmental biology, relying on the coordinated use of specific stem cell types and precise culture conditions. The process begins with the selection of three key stem cell types: Embryonic Stem (ES) cells, Trophoblast Stem (TS) cells, and Extraembryonic Endoderm (XEN) cells. ES cells, derived from the epiblast, represent the future organism, while TS cells model the trophectoderm, which gives rise to the placenta. XEN cells mimic the primitive endoderm that contributes to the yolk sac. In some experimental protocols, induced XEN (iXEN) cells are used instead, which are created by transiently expressing the transcription factor GATA4 in ES cells. This approach simulates the function of primitive endoderm without needing a separate XEN cell line, offering flexibility in the experimental design.

One of the most remarkable features of this synthetic embryo model is its self-assembly, driven by cell-type-specific cadherin expression—adhesion molecules critical to cellular organization. Each stem cell type expresses a unique cadherin: XEN cells express K-cadherin, TS cells express P-cadherin, and ES cells express E-cadherin. These adhesion profiles orchestrate the spatial arrangement of cells within the aggregate. The XEN cells typically envelop the ES cells, while TS cells localize above the ES layer, recapitulating the architecture of early natural embryos. Researchers have found that manipulating cadherin expression levels—such as enhancing P-cadherin expression in TS cells—can improve the efficiency and accuracy of embryoid formation.

The physical assembly of the embryo-like structure begins with the aggregation and early culture phase. ES, TS, and iXEN cells are mixed in precisely defined ratios in specially designed microwell plates, such as AggreWells, which facilitate uniform aggregation. Over the next four days, these aggregates form cavitated epithelial compartments, morphologically resembling post-implantation mouse embryos at the E5.5 developmental stage. This stage is critical, as it sets the stage for further embryonic patterning and germ layer formation.

By Day 5, aggregates displaying proper cavitation and Anterior Visceral Endoderm (AVE) migration—a key indicator of gastrulation readiness—are selected and transferred to rotating suspension culture systems. These dynamic environments mimic the mechanical forces of the in utero milieu and support continued growth. From Day 7 onwards, the culture is supplemented with vital nutrients such as glucose to fuel development. Under these conditions, the synthetic embryos can develop through gastrulation and neurulation, reaching stages comparable to embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5). At this point, the structures exhibit remarkable complexity, including rudimentary organs such as a beating heart, neural tube, brain regions (including anterior forebrain and midbrain), somites, gut tube, and primordial germ cells.

To validate that these synthetic embryos genuinely model natural development, researchers employ robust molecular validation techniques. Single-cell RNA sequencing allows detailed comparison of gene expression profiles between synthetic and natural embryos, confirming fidelity in lineage specification and organogenesis. Additionally, functional genomics assays—such as Pax6 gene knockout—demonstrate the system’s capacity to replicate known in vivo phenotypes. In these studies, the absence of Pax6 led to neural tube and brain malformations, mirroring defects seen in natural embryos lacking this critical gene.

Beyond biochemical signaling, biophysical drivers such as differential cell adhesion and cortical tension play essential roles in the self-organization of embryoids. Cortical tension is regulated by actomyosin contractility, a force-generating cytoskeletal system. Experiments disrupting actomyosin activity—for instance, by treating the cultures with blebbistatin, a myosin inhibitor—result in malformed embryoids, underscoring the indispensable role of mechanical forces in embryonic patterning and morphogenesis.

This synthetic embryo model is significant for several reasons. It surpasses earlier gastruloid models in complexity and developmental progression, successfully achieving organized structures like the forebrain and functioning heart—features previously unattainable in vitro. Importantly, this approach enables functional studies of gene activity without the ethical and logistical constraints of working with live animals, making it an invaluable tool for understanding congenital defects and early developmental failures. Furthermore, it paves the way for human embryo modeling, offering insights into early pregnancy loss, infertility, and potential strategies for regenerative medicine by recreating early human developmental stages in controlled lab settings.

You must be logged in to post a comment.