by Iqra Sharjeel

In the realm of genetic engineering, few innovations have stirred the scientific community—and the imagination of the public—like CRISPR-Cas9. Since its discovery and application as a gene-editing tool in the early 2010s, CRISPR has evolved from a bacterial defense mechanism into a molecular scalpel capable of rewriting DNA. But science never stops. Now, a new generation of this technology—known as CRISPR-Cas9 2.0, or base editing—is making headlines for its precision, safety, and real-world potential.

This next-level CRISPR doesn’t just cut DNA; it rewrites it, one letter at a time. The implications are enormous, not only for inherited diseases but also for cancer therapy, agricultural biotechnology, and even environmental science.

In this blog, we’ll explore what makes CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 unique, how it improves upon the original version, and a real-world case study that proves it’s more than just a laboratory fantasy—it’s changing lives.

The Original CRISPR-Cas9: A Scientific Revolution

To understand CRISPR-Cas9 2.0, we must first appreciate the original. Discovered as part of an adaptive immune system in bacteria, CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) and its partner enzyme Cas9 (CRISPR-associated protein 9) allow bacteria to identify and destroy viral DNA.

Scientists quickly repurposed this system to edit the genomes of living organisms, including humans. By designing a guide RNA to target a specific DNA sequence and using Cas9 to make a double-stranded break, researchers could delete, insert, or replace genes.

This technology transformed genetic engineering. It was faster, cheaper, and more accurate than anything before. In 2020, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work on CRISPR-Cas9.

Yet, despite its power, this first-generation CRISPR had limitations.

The Problem: Blunt Tools for Delicate Jobs

CRISPR-Cas9 works like molecular scissors. It creates a double-strand break (DSB) at a specific location in the DNA, which the cell must repair. There are two main repair methods: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which is error-prone and can cause mutations, or homology-directed repair (HDR), which is more precise but only occurs under certain conditions.

This method, while groundbreaking, can lead to:

- Off-target mutations, where the wrong part of the genome is cut

- Unintended deletions or rearrangements

- Cellular stress, since double-stranded breaks are a red alert for the cell

Imagine needing to fix a typo in a book but being forced to tear out the whole page and hope the printer gets it right. That’s CRISPR 1.0 in action.

That’s where CRISPR-Cas9 2.0—or base editing—enters the story.

CRISPR-Cas9 2.0: Precision Without the Scissors

CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 represents a groundbreaking evolution in gene-editing technology, offering unprecedented precision without the need to cut the DNA. Unlike traditional CRISPR-Cas9, which uses molecular “scissors” to make double-stranded breaks in DNA, this next-generation approach focuses on chemically altering individual DNA bases—adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), or cytosine (C)—without breaking the DNA strand. This shift in technique drastically reduces the risk of unintended genetic damage and opens new doors for treating genetic disorders with greater safety and accuracy.

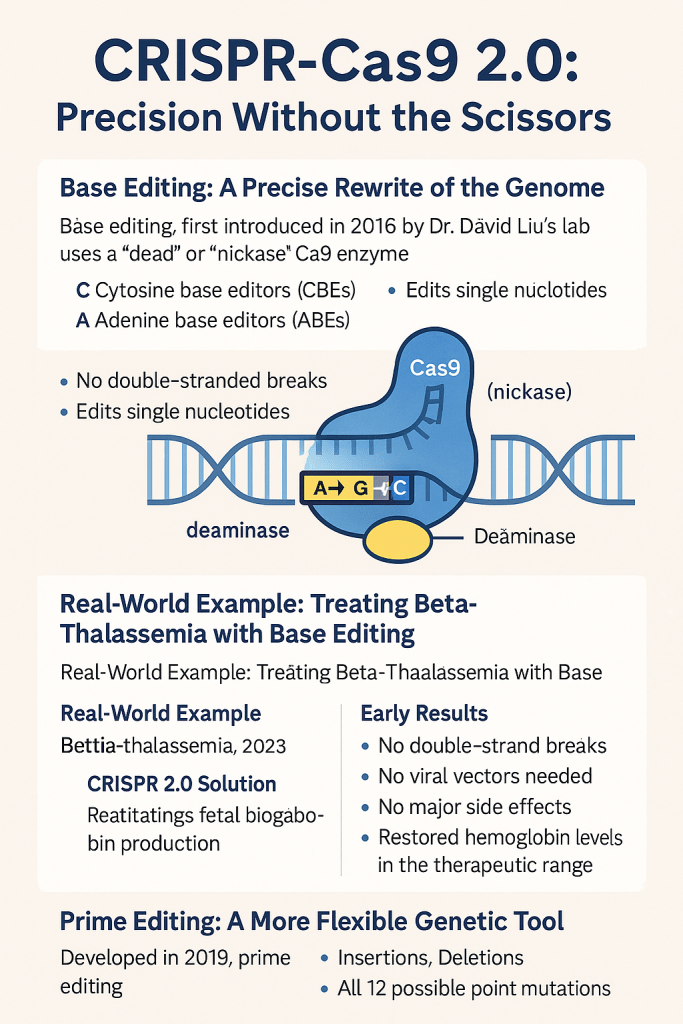

One of the central innovations in CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 is base editing, a method first introduced in 2016 by Dr. David Liu’s lab at the Broad Institute. Instead of using a fully functional Cas9 enzyme, base editing employs a modified form called a “nickase” or “dead” Cas9, which cannot cut both strands of DNA. This engineered enzyme is fused with a deaminase, a chemical modifier that changes the identity of a single DNA base. There are two primary types of base editors: cytosine base editors (CBEs), which convert cytosine (C) to thymine (T)—or, on the complementary strand, guanine (G) to adenine (A)—and adenine base editors (ABEs), which convert adenine (A) to guanine (G), or thymine (T) to cytosine (C).

This strategy of single-letter precision offers numerous advantages. Because it avoids double-stranded breaks, base editing causes significantly less stress to the genome and minimizes the risk of harmful off-target effects. Moreover, its pinpoint accuracy makes it especially suitable for correcting point mutations—single-letter genetic errors that are responsible for nearly 60% of all known human genetic diseases. As a result, CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 has emerged as a powerful and safer alternative for therapeutic genome editing, bringing us closer to effective cures for many inherited conditions.

Real-World Example: Treating Beta-Thalassemia with Base Editing

A compelling example of CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 in action is its use in treating beta-thalassemia, a severe genetic blood disorder. Beta-thalassemia arises from mutations in the HBB gene, which is crucial for producing beta-globin—a component of hemoglobin that carries oxygen in red blood cells. This mutation leads to a reduction or absence of beta-globin, causing symptoms like chronic anemia, fatigue, bone deformities, and often lifelong dependence on blood transfusions.

In 2023, Beam Therapeutics initiated a clinical trial leveraging adenine base editing to correct this genetic defect. Instead of removing the faulty gene, researchers rewrote a single A-T base pair into a G-C pair. This molecular adjustment effectively restored the production of functional hemoglobin by reactivating fetal hemoglobin—a form naturally produced before birth that can compensate for the defective adult version. The result was a notable increase in healthy red blood cell production and a reduced need for transfusions in early-stage patients.

Benefits Observed:

- No double-stranded breaks

- No need for viral vectors

- No significant side effects

- Hemoglobin levels restored to a therapeutic range

This breakthrough shows that gene editing is no longer a distant promise—it is rapidly becoming a clinical reality.

Prime Editing: A More Flexible Genetic Tool

Another remarkable advancement within CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 is prime editing, developed in 2019. Prime editing functions like a molecular “search-and-replace” tool for DNA, capable of executing a wide range of genetic edits with exceptional precision. It uses a Cas9 nickase fused to a reverse transcriptase enzyme, guided by a specialized prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA).

This platform can perform:

- Insertions

- Deletions

- All 12 possible point mutations

Unlike traditional CRISPR, prime editing does not require donor DNA templates and avoids creating double-strand breaks. Though still in its early stages of clinical application, prime editing holds vast potential for treating diseases that involve complex or multiple genetic mutations.

Ethical Considerations: Power With Caution

Despite the incredible potential of CRISPR-Cas9 2.0, it brings with it serious ethical considerations. Who will have access to these life-changing therapies? What are the long-term consequences of altering DNA? And should this technology be used for human enhancement rather than solely for treatment?

These concerns are especially relevant in light of the 2018 controversy in China, where genetically edited babies were born after CRISPR 1.0 was used for germline modification. That incident sparked global outrage and highlighted the need for strict ethical guidelines. Today, most responsible research focuses on somatic cell editing—which doesn’t affect future generations—as opposed to germline editing, which raises far-reaching moral and biological implications.

Beyond Human Health: CRISPR 2.0 in Agriculture and the Environment

Although the spotlight often shines on medicine, CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 is also transforming agriculture and environmental science.

In Agriculture:

- Development of drought- and disease-resistant crops

- Creation of non-browning fruits such as apples and mushrooms

- Precise genetic modifications without foreign DNA, potentially making these crops more acceptable than traditional GMOs

In Environmental Science:

- Engineering biosensors in plants to detect pollutants

- Editing mosquito genes to prevent reproduction and fight malaria

- Creating microbes designed to degrade plastic or absorb carbon dioxide

These applications illustrate how CRISPR 2.0 can address pressing global challenges—from food security to climate change—if implemented with careful oversight.

Looking Ahead: The Future of CRISPR 2.0

Though still in early clinical development, the future of CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 is rich with promise. Key areas under exploration include:

- Sickle cell disease treatment using base editing, with early trials showing promising results

- Gene therapy for inherited blindness, aiming to restore vision

- Reprogramming immune cells (CAR-T therapy) to more precisely attack cancer

- In vivo editing, where genes are modified directly within the human body rather than in extracted cells

As delivery systems like lipid nanoparticles and viral vectors improve, and as AI tools become more adept at designing accurate guide RNAs, the efficiency and safety of gene editing technologies will only continue to grow.

Conclusion: One Letter Can Change a Life

CRISPR-Cas9 2.0 isn’t merely a technological upgrade—it marks the dawn of a new era in medicine and biotechnology. Through tools like base editing and prime editing, we now have the power to correct genetic errors at their root, potentially curing conditions that were once deemed incurable.

The successful use of base editing in treating beta-thalassemia is living proof of what this technology can achieve. However, as we navigate this new frontier, it is crucial to proceed with caution, transparency, and a strong ethical framework. The ability to reprogram life is one of the most powerful tools science has ever created—and how we choose to use it will define the future of humanity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.