By Iqra Sharjeel

Based on article: The gut microbiome and cancer: from tumorigenesis to therapy

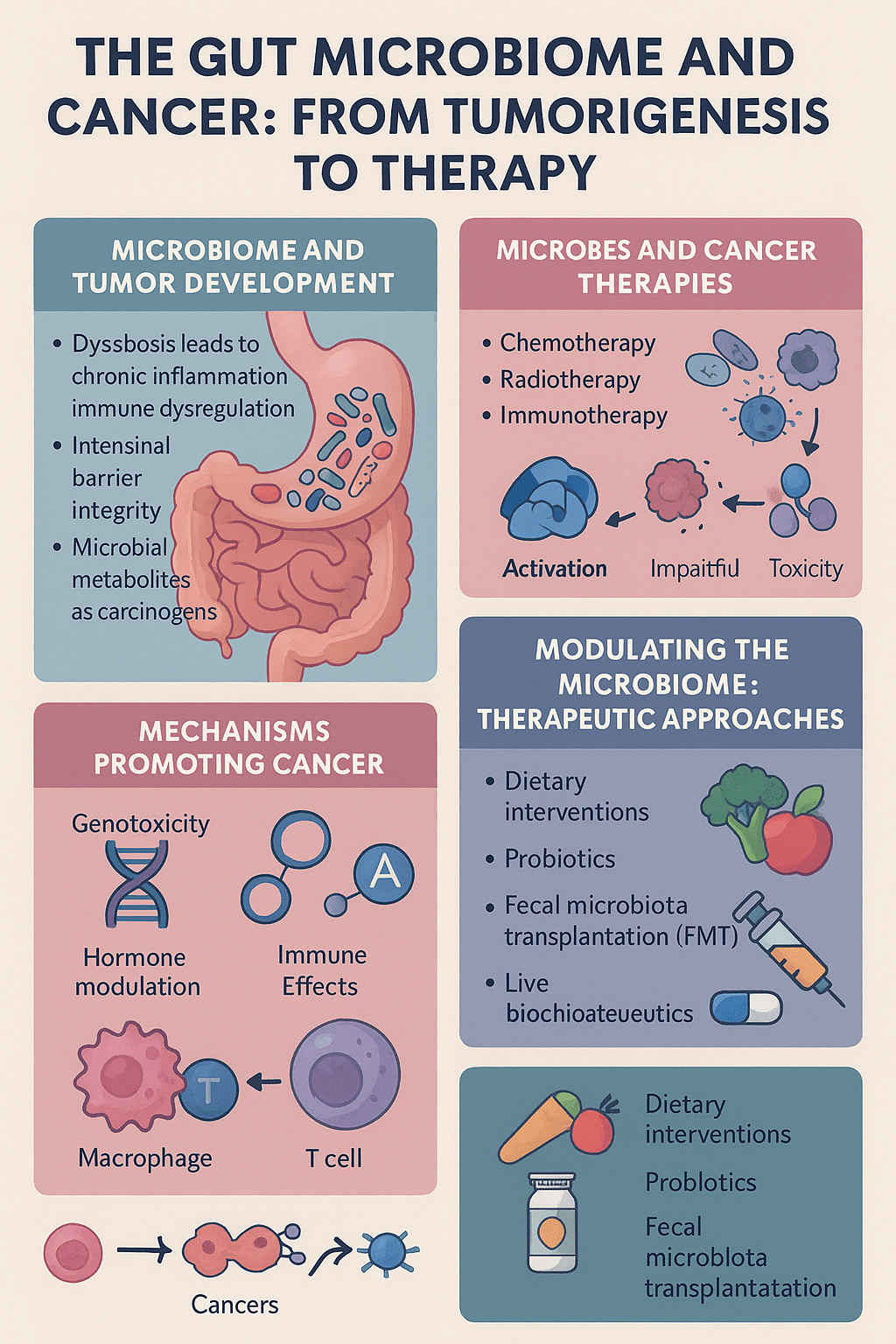

This review presents a comprehensive overview of how the gut microbiome—our internal ecosystem of microbes—interacts with cancer biology. The authors delve into mechanisms spanning from early tumor development to the success or failure of cutting-edge cancer therapies.

The Microbiome as a Cellular Partner in Cancer Initiation

The human gastrointestinal tract is home to trillions of microorganisms, collectively known as the gut microbiota. These microbes interact intimately with host tissues and play essential roles in digestion, vitamin synthesis, and immune regulation.

But this balance can be disrupted—through diet, antibiotics, stress, or genetics—leading to dysbiosis, a state in which pathogenic or opportunistic microbes overtake beneficial ones.

This dysregulation has been linked to:

Increased intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut,” allowing microbial products like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to trigger systemic inflammation.

Immune system modulation, where chronic, low-grade inflammation fuels DNA damage and tissue remodeling, creating an environment ripe for tumor development.

Microbial metabolites (like certain bile acids and ammonia derivatives) that can directly act as carcinogens or co-carcinogens in susceptible tissues.

Certain microbes—like Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal cancer—have been shown to infiltrate tumor tissue, influence gene expression, and promote metastasis.

Molecular Pathways: How Microbes Drive or Suppress Tumorigenesis

The gut microbiome plays a dual role: it can either promote or prevent cancer, depending on the microbial composition and the host context.

Key mechanisms include:

Genotoxic effects: Some bacteria produce enzymes or compounds that cause mutations in DNA. For example, Escherichia coli strains that carry the pks island produce colibactin, a genotoxin linked to colorectal cancer.

Hormonal modulation: The so-called estrobolome—the collection of microbes involved in estrogen metabolism—can affect hormone-driven cancers. Elevated deconjugation of estrogens by gut bacteria leads to higher circulating levels of active estrogen, potentially influencing breast, ovarian, and prostate cancers.

Immune surveillance disruption: Tumor-promoting bacteria can either mask cancer cells from immune detection or exhaust T-cell function, impairing anti-tumor immunity.

Microbiome–Therapy Interactions: A Double-Edged Sword in Oncology

The gut microbiota can significantly affect how patients respond to conventional and modern cancer treatments. The review examines several modalities:

a) Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy

Gut bacteria can biotransform chemotherapeutic agents, altering their efficacy. For instance, bacterial enzymes inactivate gemcitabine, a commonly used drug in pancreatic cancer. Microbes also influence how toxins are cleared from the body, affecting systemic toxicity and causing side effects such as mucositis or diarrhea.

b) Targeted Therapies

Drugs like cetuximab (anti-EGFR) and trastuzumab (anti-HER2) show variable success in patients depending on their gut microbial diversity. Certain bacterial signatures predict better drug responsiveness, while others are associated with resistance or relapse.

c) Immunotherapy (Checkpoint Inhibitors)

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (like anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4) rely on an active immune system to recognize and destroy cancer cells. Gut microbes shape this immune readiness. For example, species like Akkermansia muciniphila and Bifidobacterium longum have been linked to enhanced immunotherapy response. Microbial products engage innate immune receptors (e.g., TLRs), activate STING signaling, and train dendritic cells—crucial for T-cell activation and tumor killing.

The Language of Metabolites: Microbial Chemistry in the Tumor Microenvironment

Microbial metabolism generates a rich variety of molecules that act locally and systemically. Some of the most studied metabolites include:

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate:

Produced during fiber fermentation. Promote regulatory T-cell development, reinforce the gut barrier, and suppress inflammation. Butyrate also acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, altering gene expression epigenetically in tumor and immune cells.

- Bile acids (BAs):

Secondary bile acids, modified by gut microbes, can either promote cancer (e.g., deoxycholic acid in liver tumors) or enhance anti-tumor immunity via FXR or TGR5 receptor signaling.

- Tryptophan-derived indoles:

Metabolites like indole-3-aldehyde activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) pathway, modulating immune homeostasis and anti-tumor immunity in epithelial tissues.

The balance of these metabolites is crucial: tipping toward pro-inflammatory or carcinogenic molecules can increase cancer risk.

Engineering the Microbiome: A New Frontier in Precision Oncology

Recognizing the microbiome as a modifiable determinant of cancer risk and treatment outcomes opens new therapeutic opportunities.

Emerging interventions include:

Dietary modulation: Increasing fiber intake, reducing processed foods, and adjusting fat sources to shift microbiome profiles toward beneficial species.

Probiotics and synbiotics: Live beneficial bacteria and supportive nutrients may help restore microbial balance during or after cancer therapy.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT): Transferring gut contents from healthy donors to reestablish a resilient microbial ecosystem in patients—already showing promise in melanoma patients receiving PD-1 inhibitors.

Next-generation “live biotherapeutics”: Engineered microbes or microbial consortia tailored to produce anti-tumor metabolites or engage specific immune pathways.

Future Outlook: Toward Microbiome-Integrated Cancer Care

The review concludes by emphasizing the need to integrate microbiome research into oncology clinics. Key directions include:

Microbial biomarkers: Identifying bacterial signatures that predict cancer susceptibility or treatment responsiveness.

Companion diagnostics: Pairing microbiome profiles with specific drugs for personalized therapy.

Longitudinal monitoring: Tracking microbial dynamics before, during, and after treatment to guide interventions.

Large-scale, controlled clinical trials are essential to validate microbial interventions and build standardized protocolsfor microbiome analysis and modulation.

Final Reflection

“Cancer is not just a genetic disease—it is also a microbial one.”

This review powerfully illustrates that the gut microbiome is not a passive bystander but an active player in cancer biology. It influences not only who gets cancer, but also how tumors behave, how patients respond to drugs, and how durable the therapy is.

As oncology moves toward a future of personalized medicine, the gut microbiome may become one of its most critical allies—or, if neglected, one of its greatest obstacles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.